What would a debt financing crisis scenario look like avoided by Romania through the recently introduced fiscal measures?

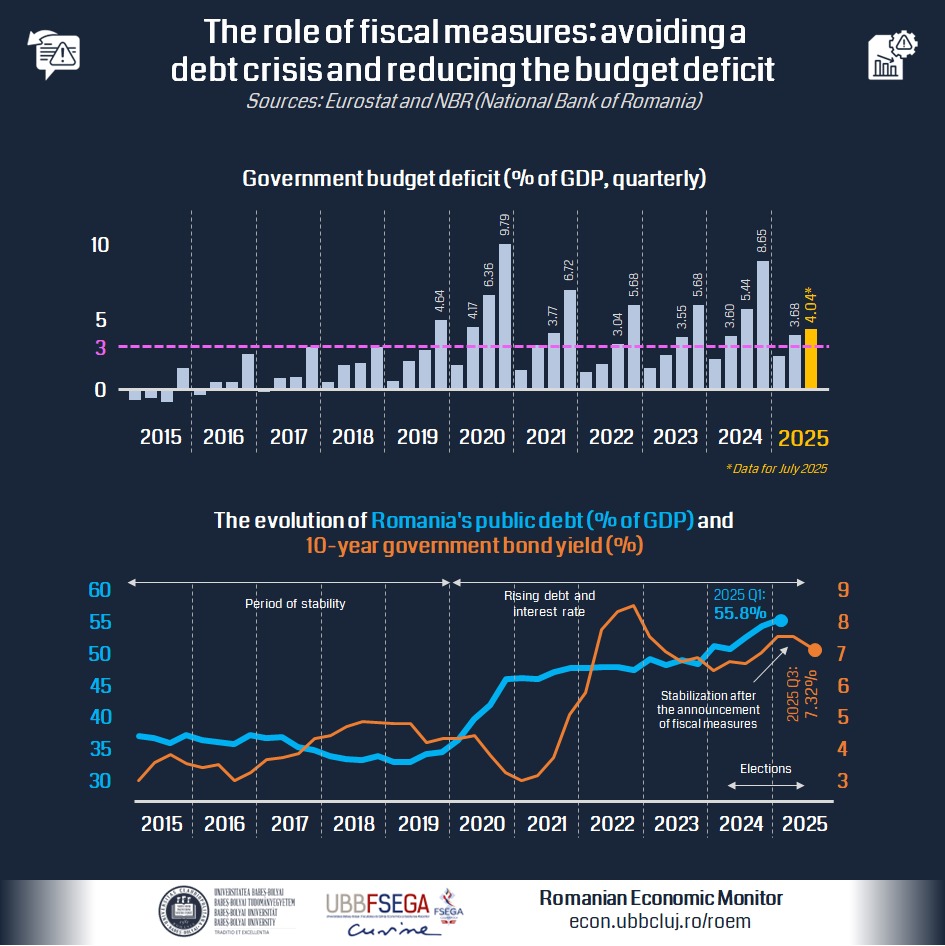

Romania’s public debt reached approximately 55% of GDP in 2024, an increase of 20 percentage points compared to 2018, while the budget deficit exceeded 8.6% last year. Maintaining a deficit of this magnitude would mean that in about 5–6 years the debt would exceed 100% of GDP. Although there are countries where public debt far exceeds this level without the immediate risk of a debt financing crisis — such as Italy, with a debt of 135% of GDP in 2024 — it is unlikely that Romania would be politically and economically capable of sustaining a significantly higher debt than it currently has.

In fact, economic analyses[1] show that for middle-income countries, such as Romania, more than half of the cases of default occur at external debt levels below 60% of GDP. The sustainability of countries’ public debt is generally determined not only by their economic capacity but also by the quality of their public and political institutions. If a government considers that debt repayment is becoming too costly economically and politically, which is increasingly likely as public debt rises, it may decide to declare insolvency and negotiate a partial debt reduction with the state’s creditors. In recent years, external creditors’ confidence in the ability of Romanian public institutions to manage a large budget deficit has weakened, which could have led to a public debt financing crisis with severe economic effects—a scenario that has been avoided for the time being following the introduction of austerity measures. These measures represent a significant burden for the population. It is important to be aware of the alternative scenario, i.e., the situation that Romania has avoided by applying these fiscal measures.

The scenario of a debt financing crisis

What does such a scenario, which Romania has so far avoided, look like? If Romania’s external creditors lose confidence in the government’s ability or willingness to finance public debt, they may in turn refuse to finance budget deficits and sell their government bonds on secondary markets. This scenario may have three main consequences.

Firstly, in such a context, the government is forced to drastically reduce its spending and/or increase its revenues, i.e. implement even more severe austerity measures. This would mean a significant reduction in demand on domestic markets, leading to a deep and prolonged economic recession. Currently, thanks to the fiscal measures introduced in Romania, financial markets seem willing to finance a deficit of over 7-8% of GDP in 2025, but with the implicit condition that it will gradually decline in the future. Without this confidence, a sudden halt to lending on this scale would have catastrophic economic effects.

Secondly, the decline in the price of government bonds, a direct consequence of the loss of confidence in financial markets, would significantly weaken the Romanian banking sector. Public debt is a significant component of Romanian banking assets, and if it loses value, the risk of insolvency and banking crisis increases. A domestic financial crisis would hit the real economy hard and put a lot of pressure on a government with limited economic options.

Third, high economic and financial volatility can reduce the volume of foreign direct investment (FDI), which reduces the potential for economic growth in the medium and long term. Weakening economic relations with partner countries can reduce capital and technology transfers, making it harder to bounce back from an economic crisis.

A relevant example in this regard is Greece, another EU Member State that has experienced an extremely severe debt crisis. After the Greek government revealed that it had published false figures, underestimating public debt, which reached approximately 130% of GDP in 2009, foreign investors began to leave the country, and Greece needed financial assistance from the IMF and its European partners. Furthermore, following negotiations between the Greek government and its creditors, the value of public debt held by private banks was reduced by 50% in 2011, seriously affecting the banks’ exposure. Alongside these emergency measures, the government was forced to introduce extreme austerity measures: between 2009 and 2018, VAT, income tax, excise duties, and property taxes were increased several times, and government spending was reduced by approximately 30% (-€38 billion) between 2009 and 2014. Greek banks went through a period of intense financial stress, exacerbating the economic crisis, and the banking sector needed repeated rounds of consolidation and recapitalization to survive this period.

The consequence of these events was a severe humanitarian and economic crisis: Greece’s GDP contracted by approximately 25% between 2009 and 2012, and the recovery has been extremely slow, with the GDP still more than 10% below its 2009 level. Household consumption expenditure fell by 30% between 2010 and 2015, and the unemployment rate rose from 9.7% in 2009 to 27.6% in 2013. Although Romania began adopting austerity measures before reaching the critical point Greece found itself in 2009, and has not yet needed external financial assistance, avoiding a similar scenario requires continued responsible fiscal policies in the years to come.

The first signs of normalization

In Romania, signs of a potential public debt financing crisis became increasingly apparent during 2024. After the interest rate on long-term (10-year) government bonds rose from 3% in 2021 to 7% in October 2024, reflecting both the unsustainable increase in the budget deficit and tighter monetary policy, it went through a period of high volatility after the elections at the end of 2024, even reaching 8.5% at one point during the 2025 presidential elections. Although there has been some normalization following political stabilization, with volatility decreasing, interest rates remain high, at over 7%. This situation means that the state is borrowing long-term—which is essential from the perspective of investment and economic growth—at high costs, and restoring budgetary balance remains essential in order to have access to cheaper loans.

Similarly, the price of insurance against sovereign default (Credit Default Swap, CDS) rose by around 60% between 2019 and 2024, as structural budgetary problems worsened. Furthermore, between October 2024 and May 2025, it rose sharply by approximately 50%, reflecting the volatility of the political situation. This increase actually represents the higher probability that financial markets attached to a default by the state. After the 2025 elections, however, CDS prices fell to roughly the same level as in October 2024, indicating some recovery, but still at a higher risk than in 2019.

Although external creditors now have more confidence in the government and its continued ability to repay its debts, long-term confidence can only be maintained through responsible fiscal policies and credible, consistent, and, in the current context, as fair as possible implementation of the announced fiscal measures.

[1] Kenneth S. Rogoff and Carmen M. Reinhart, De data asta e altfel, Romanian ed., trans. Smaranda Nistor (București: Editura Publica, 2012), 608, ISBN 978‑973‑1931‑90‑6.