Romania between structural imbalances and the urgent need for fiscal reform

Starting in 2015, the overall orientation of Romania’s fiscal and budgetary policy underwent a major shift, with lasting implications for macroeconomic balances. The period from 2009 to 2015 was characterized by a clear process of fiscal consolidation, with budget and current account deficits brought below the 1% threshold in 2015. This interval, in retrospect, stands out as a true “landmark moment” for macroeconomic stability. At that time, Romania was on a trajectory that, barring significant deviations, could have allowed for a potential euro area accession around 2019.

However, given this stability, there was an accelerated relaxation of fiscal discipline: the political class viewed the margins created as opportunities for expansionary policies, without a rigorous analysis of their sustainability. This was followed by a series of tax cuts (notably VAT reductions), substantial increases in public sector wages, and other pro-cyclical measures. In the short term, these actions stimulated economic growth, reinforcing the false impression that the new approach was “functional.” This dynamics generated a vicious cycle of budgetary expansion fueled by conjunctural optimism—a pattern well known from the experiences of certain Latin American emerging economies.

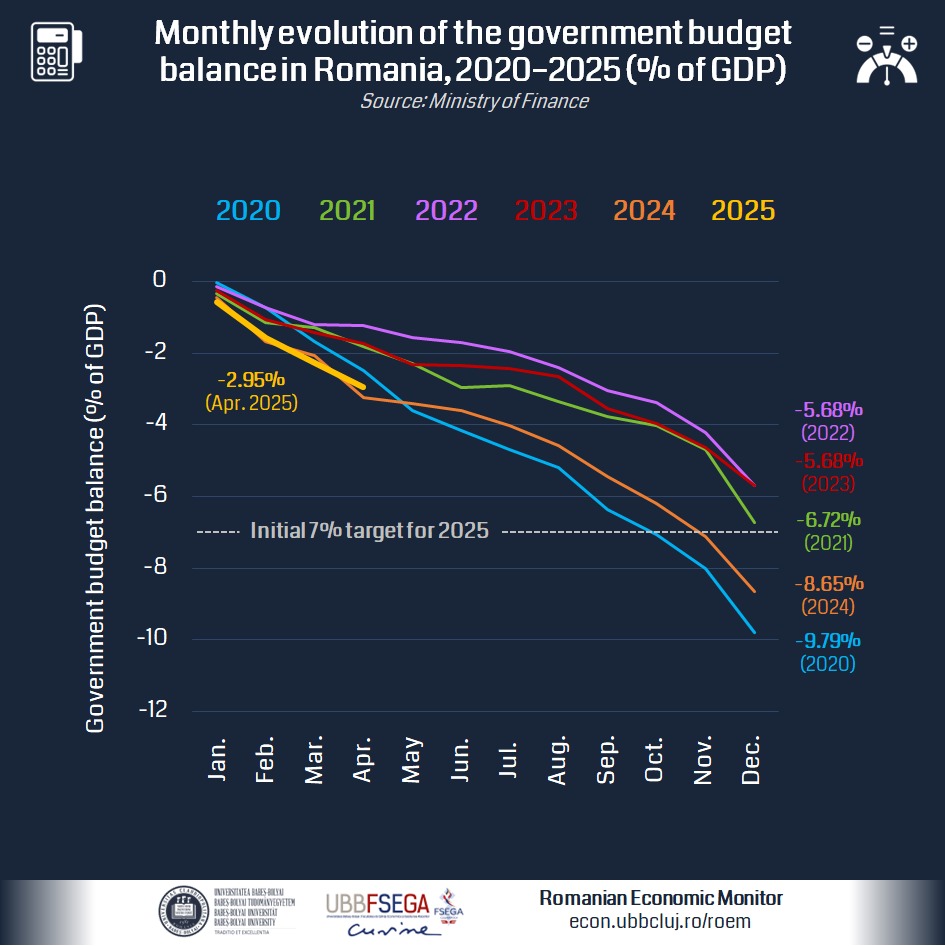

By 2019, the negative effects of this policy orientation had already become visible: the public budget became unbalanced, and the state apparatus expanded considerably. Subsequent crises, starting with the effects of the pandemic in 2020, only exacerbated previously accumulated vulnerabilities.

Thus, Romania has become the country with the greatest internal and external macroeconomic imbalances in the entire EU: Both the budget deficit and the current account deficit account for the largest shares of GDP. These imbalances increase sovereign risk, which is reflected in higher financing costs for the state—in other words, a higher risk premium—that, in turn, places additional pressure on an already vulnerable budget.

There are many reasons for the European Commission’s tolerance of this attitude. On the one hand, there was a desire to avoid escalating tensions in a sensitive domestic electoral context. On the other hand, however, the decision to grant Romania an exceptionally long period—seven years—to bring its deficit back below the 3% of GDP threshold also reflects strategic considerations. Romania occupies a key geopolitical position in today’s regional context, shaped by Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, and its staunchly pro-European and pro-NATO orientation is an important factor in its political and institutional evaluation by European partners. Accordingly, the Commission’s flexibility can also be seen as a recognition of Romania’s strategic role in the region. However, the Commission’s patience now appears to have run out. The agreed commitments must now be honored: fiscal data published for the first months of 2025 indicate the need for decisive intervention to avoid a repeat of the budget deficit trajectory seen in previous years. Although the initial deficit target of 7% is increasingly difficult to achieve, a significant reduction compared to the previous year would already signal that Romania is assuming responsibility for the difficult path toward restoring budgetary balance.

The size of the state, both in terms of revenues and expenditures, must, however, be adjusted in a balanced and strategic manner. In the current fiscal context, Romania requires a state of larger dimensions than at present—specifically, in the sense of mobilizing significantly higher public revenues, while at the same time avoiding the risk of excessive and inefficient expansion of expenditures.

Maintaining a relatively smaller state compared to the European average can support both the accumulation of domestic capital—through the reinvestment of local revenues—and the attraction of foreign direct investments, given that Romania still has a low level of capital relative to the number of employees. What is needed, therefore, is not an oversized state, but rather a more efficient and better-funded state, oriented towards the provision of high-quality public services.

Achieving fiscal equilibrium will require the simultaneous implementation of at least five core measures. The first and most important is fiscal reform. The five necessary directions are as follows:

- Reducing the size of the state administration.

- Increasing budget revenues by raising effective average tax rates.

- Enhancing tax collection through improved fiscal compliance.

- Continuing the digitalization of the National Agency for Fiscal Administration (ANAF) and increasing the efficiency of controls.

- Efficient utilization of European Union funds.

In the sections that follow, the RoEM team details the key principles that should guide the fiscal reform process.

Measure Zero: Rationalizing State Expenditures on Personnel and Investment

The state administration must be technically downsized, even though there are clear limits to such reductions. Personnel expenses can and should be rationalized by eliminating various bonuses, while certain early-stage investments (such as the construction of stadiums or other prestige projects that yield low financial returns) can be postponed. Sadly, however, these measures will not prove sufficient to put the state budget on a sustainable trajectory, additional immediate measures primarily aimed at increasing budget revenues are also necessary.

- Increasing Budget Revenues by Raising the Average Effective Tax Rates

1.1. Corporate Taxation

The current corporate taxation system in Romania is profoundly unpredictable. Frequently announced changes on very short notice directly undermine one of the essential needs of the business environment: fiscal predictability. Furthermore, fragmented, ad hoc adjustments have caused significant distortions within the economy.

A telling example is the very structure of corporate taxation, which currently operates under three main regimes (in addition to other exceptions):

- the microenterprise regime, where the tax base is turnover, and the qualification thresholds change from one year to another;

- the profit tax for regular companies;

- and a minimum tax of 1% on turnover for companies with revenues over 50 million euros.

This differentiation of the fiscal regime based on company size, combined with frequent changes to the qualification criteria, clearly erodes the competitiveness of companies. Added to this is the fact that Romania has the lowest VAT collection rate in the European Union, largely due to the slow digitalization of ANAF.

It is clear that simply adjusting the rates will not lead to significant results. What is needed is a structural reform of corporate taxation that reduces market distortions and eliminates the negative effects caused by unpredictability. One possible direction would be the introduction of a unified corporate taxation system, in which the emphasis is not necessarily on increasing rates, but rather on stricter regulation of deductible expenses and ensuring a fair tax base. Uniformity should be the general rule, however, certain temporary and targeted exceptions can be justified in a well-calibrated manner—for example, in the case of start-ups or young entrepreneurs, to support their entry into the market.

In addition, clear and rigorous regulation is needed for situations in which companies register negative equity, especially regarding the repayment of loans granted by shareholders. International examples show that additional revenues are not generated by increasing tax rates, but rather by closing tax loopholes related to the deductibility of expenses, financing through shareholder loans, or the extension of the cash accounting VAT mechanism.

The RoEM team strongly recommends a thorough reform of corporate taxation, one that goes beyond mere parametric adjustments of rates. This reform is inevitable. Although it will not generate significant additional revenues immediately, it is essential for restoring equity, predictability, and the functionality of the tax system, and it should be prepared and implemented as soon as possible.

1.2. Consumption Taxation

In the current macroeconomic context, it is advisable for the fiscal focus to be placed more on the taxation of consumption rather than on labour. An essential argument for this repositioning is the accelerated increase in consumption in Romania in recent years, especially the demand for imported goods and services. This type of consumption has contributed significantly to the deterioration of the external balance—reflected in growing trade and current account deficits. In such a context, increasing the taxation of consumption can have a double beneficial effect: it generates additional fiscal revenues and discourages excessive consumption of (imported) products.

In the spirit of simplifying the tax system and aiming to immediately increase budget revenues, we propose the introduction of a single VAT rate of at least 21%. This measure would impose a significant additional burden on lower-income individuals, which is why we recommend, in parallel, the introduction of a progressive personal income tax (see chapter 1.4). This progressive tax could compensate not only for the additional tax burden on the lower-income population but also for the inflationary impact caused by the VAT rate increase.

1.3. Taxation of Labor

We recommend the introduction of a moderate form of progressive income taxation for individuals, including special pensions, correlated with a reform of the social contributions system. This progressivity should be balanced and carefully calibrated so as not to discourage work, investment in human capital. The objective is to strengthen fiscal equity without affecting economic dynamics, in parallel with a fairer redistribution of the tax burden among income categories, correlated with the reform of the social contributions system and an increase in the VAT rate. Progressive taxation also helps reduce income inequalities and thus temper social tensions. One possible way to introduce progressive taxation would be a dual system, with incomes below a certain threshold having a lower marginal rate compared to incomes above this threshold. Several EU countries, such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, use such a dual system of progressive taxation.

For the lowest incomes, the income tax rate could be reduced below 10%, while for high incomes this rate could reach up to 20–25%. However, it is essential that progressivity applies to aggregated incomes, which are currently not calculated by ANAF. The progressive income tax could be extended to all types of income, including pensions. Additionally, the prohibition of combining pension and salary in the public sector could be considered.

Another important aspect is that, at present, all social insurance funds are in deficit and are covered from the general budget, which makes the maintenance of their administrative separation debatable. Partially unifying income tax with social contributions could bring greater efficiency and equity.

1.4. Taxation of Wealth

Property taxes are low and flat. Here, too, a slight progressivity is advisable: higher rates for a second home, for high-value vehicles, etc. Such measures can contribute to social equity without creating major fiscal pressures. It is important to mention that wealth taxes constitute revenues for local authorities, and these additional revenues would most likely be spent at the local level. Therefore, it would be necessary to regulate the redistribution rate of other taxes, so that the surplus from wealth taxes contributes, on a net basis, to central budget revenues.

- Other essential measures for fiscal rebalancing

In the absence of other structural measures, fiscal reform will be neither economically effective nor politically sustainable. Institutional and administrative reforms are needed to support collection, transparency, and efficiency in the use of public funds.

2.1. Increasing the degree of collection of taxes and duties

Although the introduction of the e-Invoice and e-Transport systems represented major progress, they must be complemented with additional measures:

- expanding control over VAT evasion through chains of intracommunity transactions,

- active identification of tax evasion through risk analyses,

- incentives for voluntary compliance.

2.2. Digitalization of ANAF and increasing the efficiency of inspections

Continuing the digitalization of ANAF is essential for prevention, not just for sanctioning:

- a unified and user-friendly platform for taxpayers is necessary,

- integration of fiscal and social databases (for example, integrating data on salaries and realized pensions),

- automation of verification and reimbursement processes.

2.3. Making the most of EU funds

Romania accesses European funds below its potential. There is a need to:

- simplify procedures for beneficiaries,

- reduce bureaucracy,

- continuous professional development of staff involved in project design and implementation,

- alignment between national investment strategies and EU funds

2.4. Reduction of the state apparatus

The budgetary apparatus is oversized and inefficient. In addition to numerical reductions, the following are recommended:

- reorganization of state-owned companies, especially those that are operating at a loss;

- administrative and territorial reform, carried out in a manner that is fair from the perspective of minorities and local democracy, could also generate significant budgetary savings.

- restructuring redundant functions,

- regular performance evaluation of public institutions,

- digitization of administrative processes to reduce dependence on staff.

Conclusion

Romania can no longer afford to delay fiscal reform and budget consolidation. In a climate of global economic uncertainty and increased domestic pressures, ad hoc solutions are no longer sufficient. The European Commission, rating agencies, and financial markets are closely monitoring every fiscal policy decision, and the room for maneuver has shrunk dramatically. The time for vague promises or delayed approaches is over—clear, credible, and rapidly implemented measures are needed. These measures require a systemic, coordinated, and transparent approach—with political support, but also with technocratic responsibility.

We highlight two aspects that are of major importance in introducing the fiscal measures discussed. First, urgent decisions are needed on measures to increase tax revenues, which must be implemented as soon as possible. Second, particular attention should be paid to both the intensity and the form of these measures, as in a fragile external environment they could easily push the economy into a negative cycle.